The Human Rights-based Approach to the U.S. Policy in Sudan

June 19, 2013

This week the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission held a hearing in which several experts from both the government and civil society organizations testified about the current human rights situation in Sudan. The hearing was chaired by James McGovern, a democratic representative from Massachusetts, and Frank Wolf, a republican representative from Virginia. The first panel to testify was made up of government officials including Larry André, the Director of the Office of the Special Envoy for Sudan and South Sudan, Bureau of African Affairs at the U.S. Department of State and Nancy E. Lindborg, Assistant Administrator, Bureau for Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance at the U.S. Agency for International Development, whereas the second panel was made up representatives of private organizations including John Prendergast, the Co-Founder, Enough Project, and Co-Founder, Satellite Sentinel Project, Ken Isaacs, Vice President, Programs and Government Relations at Samaritan’s Purse, E.J. Hogendoorn, Deputy Director, Africa at the International Crisis Group, and Jehanne Henry, Senior Researcher on Sudan, Africa Division at Human Rights Watch.

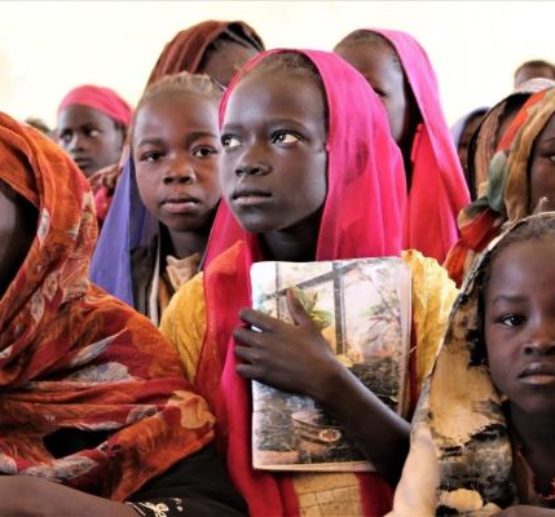

The meeting began with an overview of the situation citing the well-known numbers of 2.3 million displaced persons, 300,000 of whom have fled to Chad, and noting the extreme escalation of violence especially in Darfur, Blue Nile, and South Kordofan that has recently taken place. In fact, the testimony revealed that since January, 2013 there has been a 50% swell in IDP camps in Darfur. Although some of the fighting is inter-ethnic or between rival militias, much of the violence is perpetrated by the government itself, which carries out aerial bombardments and scorched earth tactics against its very own citizens. Not only does the government carry out direct attacks and supply militia groups that do, but also restricts humanitarian access to the displaced and needy within Sudan, while also limiting civil society and imprisoning journalists and political dissenters. The displaced all around Sudan face horrendous humanitarian conditions. Ms. Lindborg stated in her testimony that 5 million people (15% of Sudan’s total population) is now in need of humanitarian assistance, 32% of children in Sudan are underweight, which has led to 35% of the children having stunted growth. In the face of statistics like these and the fact the conflict has now been going on for 10 years with no sign of abating, it is now more important than ever that strong and effective international action is implemented.

Although the hearing covered many different topics throughout the proceedings the co-chairs continued to bring up the question: what concrete actions can the U.S. take to improve the humanitarian crisis? This important question needs to be answered if the crimes against humanity, genocide, and war crimes are going to be put to an end. The general consensus was that a comprehensive peace agreement was needed among all parties, since it was unlikely one side or the other can win militarily and regional approaches to peace would not work either. This process according to the first panel would include the cessation of hostilities followed by an inclusive political process. Mr. André called for a “unified, holistic approach” to the peace process. While creating a comprehensive peace process sounds like a great idea, it is much harder to achieve in reality. Ms. Henry offered the most comprehensive list of actions the U.S. should take to end the conflict, including: (1) the appointment of a new Special Envoy to Sudan, (2) engaging with actors such as China, Qatar, and other regional actors such as the African Union, (3) push for justice and the handing over of war criminals to the International Criminal Court, (4) and working to disarm militias. Another approach was attacking the problem through the weapon supply routes, as Sudan gets many of its weapons from China, Russia, and Iran. There was also a discussion of a stringent withdrawal of non-humanitarian aid to those states who host those members of the Sudanese government who have been indicted by the ICC to attempt to pressure those countries who deal with suspected war criminals; however, is the U.S. one of these states themselves? Mr. André and Ms. Linborg were forced to defend their position on the recent invitation of Presidential Assistant and Vice Chairman of the National Congress Party, Nafie ali Nafie to Washington D.C. Although the specifics of his involvement with the genocide in Darfur are not known, he has been a senior adviser to ICC-indicted President al-Bashir for many years including serving as the head of Sudanese intelligence and in charge of the Darfur portfolio. The invitation to the nation’s capital was the Obama administration’s attempt to promote negotiations, but has been postponed indefinitely in light of Sudan’s recent failure to cooperate with South Sudan. As Mr. André stated in his testimony, there are not many people in Sudanese government who have clean pasts that the U.S. would find appropriate to hold talks with and there is an urgent need to find a comprehensive peace. Although negotiations are necessary, an invitation to Washington D.C. can be seen as a validation of a regime that has perpetrated over 10 years of violence against its own people. Congressman Wolf expressed his opinion that the idea of inviting Nafie to the capital was “immoral” and although there is a need to have negotiations, inviting Nafie to the U.S. was a step too far. The co-chairs asked each of the members of Panel II what their position on this highly controversial subject was. Even among these experts, there was division with some arguing for the high-road and not negotiating with a known criminal, whereas others argued that any chance at a solution is a step we should take. This classic trade-off between peace and justice has posed another conundrum for the U.S. to deal with.

All of these ideas have significant merit, but it is now up to the U.S. government to implement them. What will it take for the U.S. to take a moral stand and end genocide? Overall, the U.S. foreign policy needs to take into account the human rights record of the states that it deals with in order to ensure a more peaceful world. Hearings like this bring the crisis in Sudan to light and to focus the government’s attention on it, but it is now time to take real steps to make the U.S. policy in Sudan more effective. Some new proposed legislation is titled the Sudan Peace, Security and Accountability Act of 2013. This legislation has been introduced this bill on April 24, 2013. If you wish to support the bill, call your congressperson and voice your opinion. If any action is to be taken on behalf of the U.S. the government has to be aware of the will of the public to take action.