In Response to: The Women’s Peace and Security Agenda & The Impact of COVID-19 on Women Panel

Debunking Sudanese social norms & how it harms and restricts women

https://youtu.be/3D0f6bHRlYI

Last Friday, DWAG invited special guests—Ambassador Kelley Currie, Ms. Sanam Naraghi-Anderlini (on behalf of Senator Mobina Jaffer), and Ms. Niemat Ahmadi—to tackle the issues of women’s peace and security in places of conflict, specifically in Sudan, and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the virtual panel discussion, the three women, with the help of moderator Ms. Azaz Shami, presented insightful arguments about the role of women in their communities and the need for leadership and empowerment. Sharing experiences on both the ground in Sudan and in government administrations, the speakers stressed the importance of structural reforms to allow for a significant presence of Sudanese women in positions of power to achieve transitional justice and participate in the process of peacebuilding.

But not only is it vital to recognize the women’s exceptional qualities and experiences that merit leadership roles, an important part of achieving equal participation includes an acknowledgement of the harrowing challenges Sudanese women face that prevent them from participating in government affairs. Each speaker discussed a crucial part of the violence against women and the cultural barriers that restrain them and furthermore touched on the core issue that is the corrupt system of societal norms that empowers male supremacy and enforces strict control over women.

Last year in Sudan, Omar al-Bashir—the Sudanese president of 30 years known for his regime of terror, genocide, and war—was overthrown in military coup by the people of Sudan after months of endless protest. The revolution led to a new transitional government, meant to establish lasting peace and an end to violent conflicts. However, military officials from Bashir’s regime remained in power, allowing unrest and violence to ensue. Since the takeover of the interim government, repeated instances of fatal attacks at peaceful protests have happened. The people are demanding an end to the brutality of militia soldiers and calls for accountability, which have not been met. Families flee from their homes in fear, leaving hundreds of thousands displaced in camps. Hundreds have died since, and thousands have been wounded while the interim government turns a blind eye towards the militia that continues to instigate violence.

Sudan is burning, and the leadership of Sudanese women may be the solution.

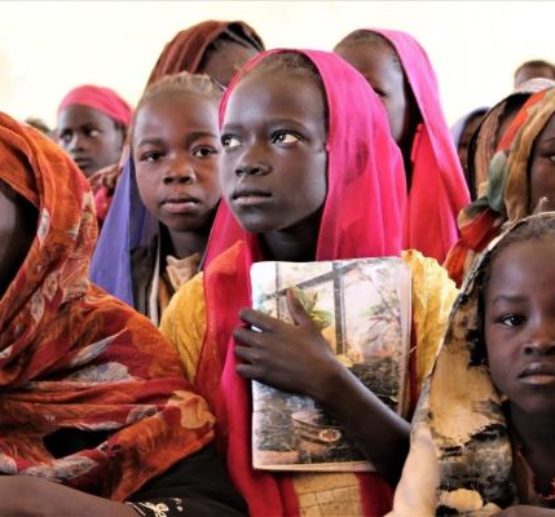

Since the beginning of the revolution, Sudanese women have been at the forefront, demanding justice and peace. Known to be leaders in all aspects of society, these women have taken the part as caretakers, heads of households, and now, the face of the Sudanese revolution. Ambassador Kelley remarks in the panel that “it was women’s collective leadership, initiative, and courage that helped to bring forth this revolution and created this opportunity for all the people of Sudan to lead a more prosperous, secure, and better life.” The role of women in the Darfur uprising has been recognized around the world, and many agree that without the courage of these women to step up and demand change, the protests may not have had the effect they had. “The fact that Sudanese women were at the forefront of the revolution…is extraordinary,” Ms. Naraghi-Anderlini added. “To be able to see that force and that power and that symbolism of peace and the fundamental issue of saying, ‘We need to change, but we’re not going to do it by behaving as you behave towards us’ and ‘the oppressed is not going to become the oppressor.’ This is a really powerful message, and it comes from women.” Stepping up as leaders of the protests, mothers and sisters of Sudan have proved themselves more than capable of leadership, acting as catalysts for positive change. As such strong and inspiring figures, Sudanese women—if given the power and authority to provide real change—could truly make huge strides for peace and security in Sudan for their people.

“There is a juxtaposition of power.”

Their roles in activism and politics, as well as in their own communities, should merit a seat at the table that determines their future, yet they remain on the sidelines. Why is that? As Ms. Naraghi-Anderlini said, the government is “still refusing to have [women] recognized as independent delegates.” Those in power, who have the resources and the responsibility to help, are present but absent when needed most. It is the least powerful—the women without resources, power, or money—who take the burden of responsibility. And yet, as Ms. Ahmadi mentioned afterward, only 12% of the peace table included women, a subtle message from the interim government that Sudanese women are not capable, despite their active part in peacebuilding.

The reason behind the disregard stems beyond the misogyny typically seen in other Western countries. Social norms, particularly formed from Bashir’s grasp on Sudanese culture, prohibit and target women to such an abusive extent that the path to equal participation may easily seem impossible.

The most degrading social norm persists in the sustenance of gender-based violence or GBV. GBV refers to violence against women, including rape, domestic abuse, sexual harassment, and sex trafficking. GBV is typically deeply rooted in gender inequality. One of the most notable human rights violations, gender-based violence continues to exist in places like Sudan. Moreover, there happens to simultaneously be an acceptance of GBV within communities. Women are encouraged to tolerate violence and wife beatings are deemed acceptable. Those in intimate relationships are told to withstand physical violence and forced intercourse.

Ms. Niemat Ahmadi mentions that “for the last 18 years, women have been subject to the most brutal [form] of attack. The former regime of al-Bashir has used rape systematically and as a deliberate policy of state against its own people, knowing that women in Darfur represent the center of society and the center of the family.”

Darfur women are victims of a cycle of violence that targets them for their gender. Knowing this, former president al-Bashir has repeatedly manipulated state laws to allow the conformity of GBV to demoralize and attack women. It is “the culture of the promotion of violence against women and the immunity that is associated with it because it had become a state policy,” says Ms. Ahmadi. “Women have been subjected to not only the direct harm, as a result of targeting them and attacking them, but also the psychological and social stigma that is associated with rape [and] the harm they have experienced from the attack on their communities.” For 18 long years, the consequences of constant attacks are bound to be seen for generations to come. Moreover, the lawlessness affects not only women but also encourages a sense of invincibility and superiority among men. Bending the law to their will, male supremacy takes hold into society as women are further seen as incapable and powerless. The generational trauma and stigma as well as the psychological damage done to victims create an endless cycle of violence that brutally tears Sudanese women apart.

The roles they are expected to take are also meant to degrade their status in society. With the expectation that they must be unhindered by the violence that plagues their peers and themselves, the women must conform to conventional roles as mothers, sisters, nurses, caretakers, teachers, housekeepers, and cooks rather than envision themselves as leaders or politicians. Those who do lead are restricted and abused by legal and moral prohibitions that control what they wear, say, see, or do, consequential to flogging or, in rare cases, stoning. While the end of al-Bashir’s rule led to a repeal of the laws, the discriminatory legal framework that continues and the societal implications they bore demand more work to be done.

The women in Darfur face immense challenges in the fight against inequality, yet they possess a distinctive strength despite the obstacles.

The roles that are imposed to instill inferiority and submission instead created strength, bravery, and protectiveness. In the panel, Ms. Naraghi-Anderlini spoke of a peculiar discussion she had with a UN colleague, who asked Darfur women why they went out to collect firewood and risk being raped. “Well,” she recounted, “If we go, we risk being raped. If the men go, they risk being killed. So we will do this.”

Their admirable resilience could be the solution to finding lasting prosperity in Darfur, but they should not fight on their own. The international community must step in to allow the equal participation of women in the peacebuilding and decision-making processes.

They fought for it. They have earned it. They deserve it.

The need for structural reforms is long overdue and the international community has turned a blind eye towards the injustice for far too long. Without the active and equal participation of women in politics, Sudan may never get to grow and change for the better.

By: Janus Kwong